Welcome

Dear Students,

Welcome to the programming course in theoretical chemistry. This class builds on the bachelor lecture "Programming Course for Chemists" and assumes that you are already familiar with the basic principles of Python and the numerical algorithms explained there.

According to current planning, the lecture will take place

- every Monday from 10:15 to 11:45

and the corresponding exercise

- every Thursday from 12:15 to 13:45.

Syllabus

A preliminary syllabus is shown below. This can and will be continously updated throughout the semester according to the progress.

| Week | Weekday | Date | Type | Topic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mon. | Apr. 25 | Lecture | Fundamentals I |

| 1 | Thur. | Apr. 28 | Lecture | Fundamentals II |

| 2 | Mon | May 2 | Lecture | SymPy: Basics |

| 2 | Thur. | May 5 | Lecture | SymPy: Applications |

| 3 | Mon. | May 9 | Lecture | Fourier Transform I |

| 3 | Thur. | May 12 | Lecture | Fourier Transform II |

| 4 | Mon. | May 16 | Exercise | Exercise 0 |

| 4 | Thur. | May 19 | Lecture | Fourier Transform III |

| 5 | Mon. | May 23 | Exercise | Exercise 1 |

| 6 | Mon. | May 30 | Lecture | Fourier Transform IV |

| 6 | Thur. | Jun. 2 | Lecture | Eigenstates I |

| 7 | Thur. | Jun. 9 | Lecture | Eigenstates II |

| 8 | Mon. | Jun. 13 | Exercise | Exercise 2 |

| 9 | Mon. | Jun. 20 | Lecture | Eigenstates III |

| 9 | Thur. | Jun. 23 | Lecture | Eigenstates IV |

| 10 | Mon. | Jun. 27 | Lecture | Quantum Dynamics I |

| 11 | Mon. | Jul. 4 | Lecture | Quantum Dynamics II |

| 11 | Thur. | Jul. 7 | Lecture | Quantum Dynamics III |

| 12 | Mon. | Jul. 11 | Lecture | |

| 12 | Thur. | Jul. 14 | Lecture | |

| 13 | Mon. | Jul. 18 | Exercise | Exercise 3 |

| 13 | Thur. | Jul. 21 | ||

| 14 | Mon. | Jul. 25 | Lecture | |

| 14 | Thur. | Jul. 28 |

Technical notes

Python Distribution

We recommend to use an Anaconda or Miniconda Python environment. Your Python version for this class should be at least 3.5 or higher. The installation of Anaconda is also shown in the following video:

Integrated Development Environment (IDE) or Editor recommendations

-

- will be automatically available after you have installed Anaconda/Miniconda.

- if you are not yet familiar with Jupyter notebooks, you can find many tutorials in the web, e.g. Tutorial.

-

- is a full Python IDE with the focus on scientific development.

- will be automatically installed if you install the full Anaconda package.

-

- is a more lightweight text editor for coding purposes and one of the most used ones.

- Although it is officially not a real IDE, it has almost all features of an IDE.

-

- commercial (free for students) IDE with a lot of functionalities.

- is usually more suitable for very large and complex Python projects and can be too cumbersome for small projects like the ones used here in the lecture.

-

Vim/NeoVim

- command-line text editor which is usually pre installed on all unix-like computers.

- can be very unwieldy at the beginning, since Vim has a very large number of keyboard shortcuts and is not as beginner friendly as a typical IDE or Jupyter notebooks.

- is extremely configurable and can be adapted with a little effort to a very extensive and comfortable editor.

- still one of the most used editors.

During the lecture we will use different Python libraries. Therefore it is necessary that you install these libraries.

Dependencies

- NumPy

conda install matplotlib

- Matplotlib

conda install -c anaconda numpy

- SciPy

conda install -c anaconda scipy

- SymPy

conda install -c anaconda sympy

- pytest

conda install -c anaconda pytest

- ipytest

conda install -c conda-forge ipytest

- Hypothesis

conda install -c conda-forge hypothesis

Why Python?

Popularity

Python is one of the most widely used programming languages and is particularly beginner-friendly.

The following figure shows the popularity of some programming languages.

Popularity of common programming languages. The popularities are taken

from the PYPL index

Requires often fewer lines of code and less work

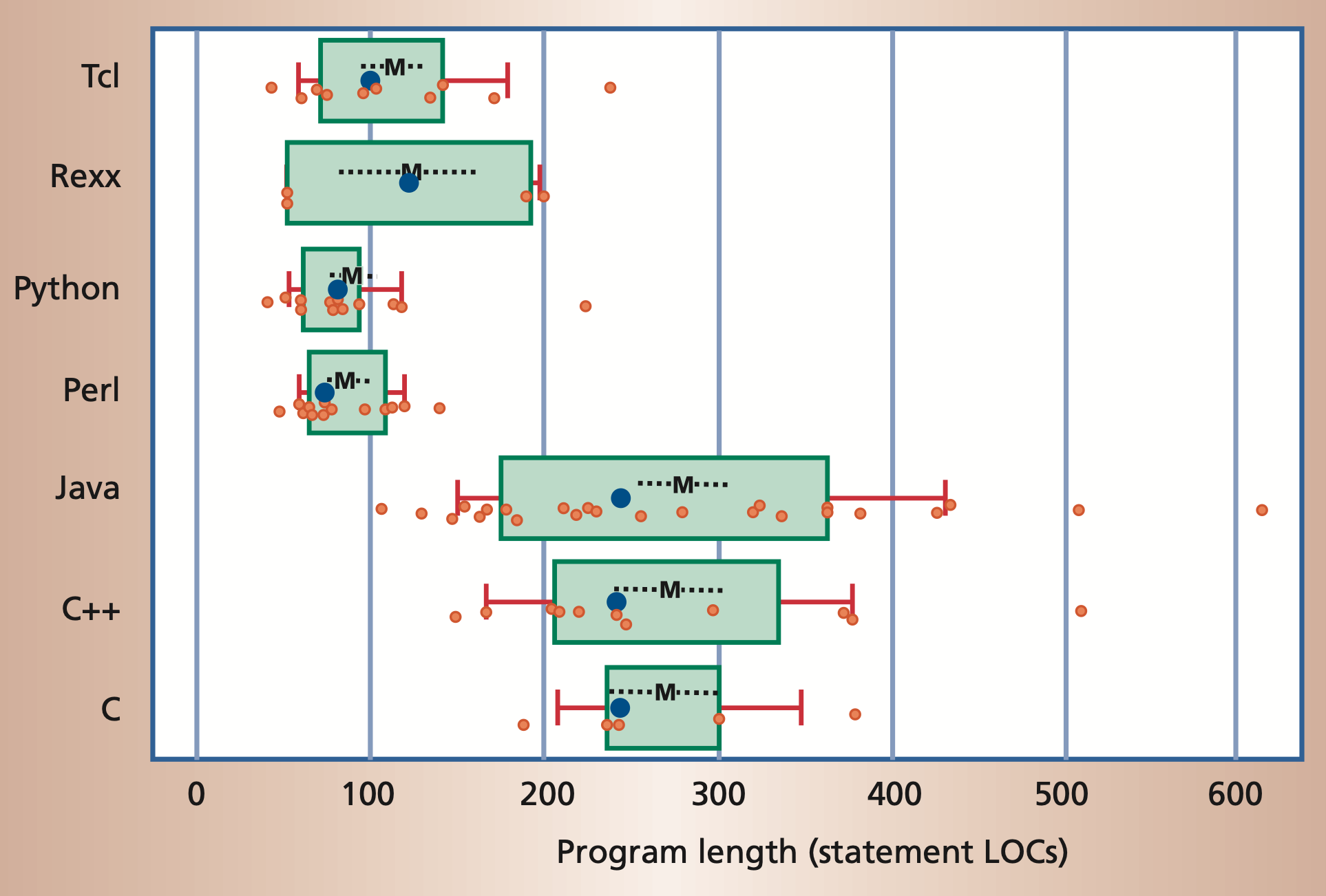

Python often requires significantly fewer lines of code to implement

the same algorithms than compiled languages such as Java or C/C++.

Program length, measured in number of noncomment source lines of code

(LOC).

Program length, measured in number of noncomment source lines of code

(LOC).

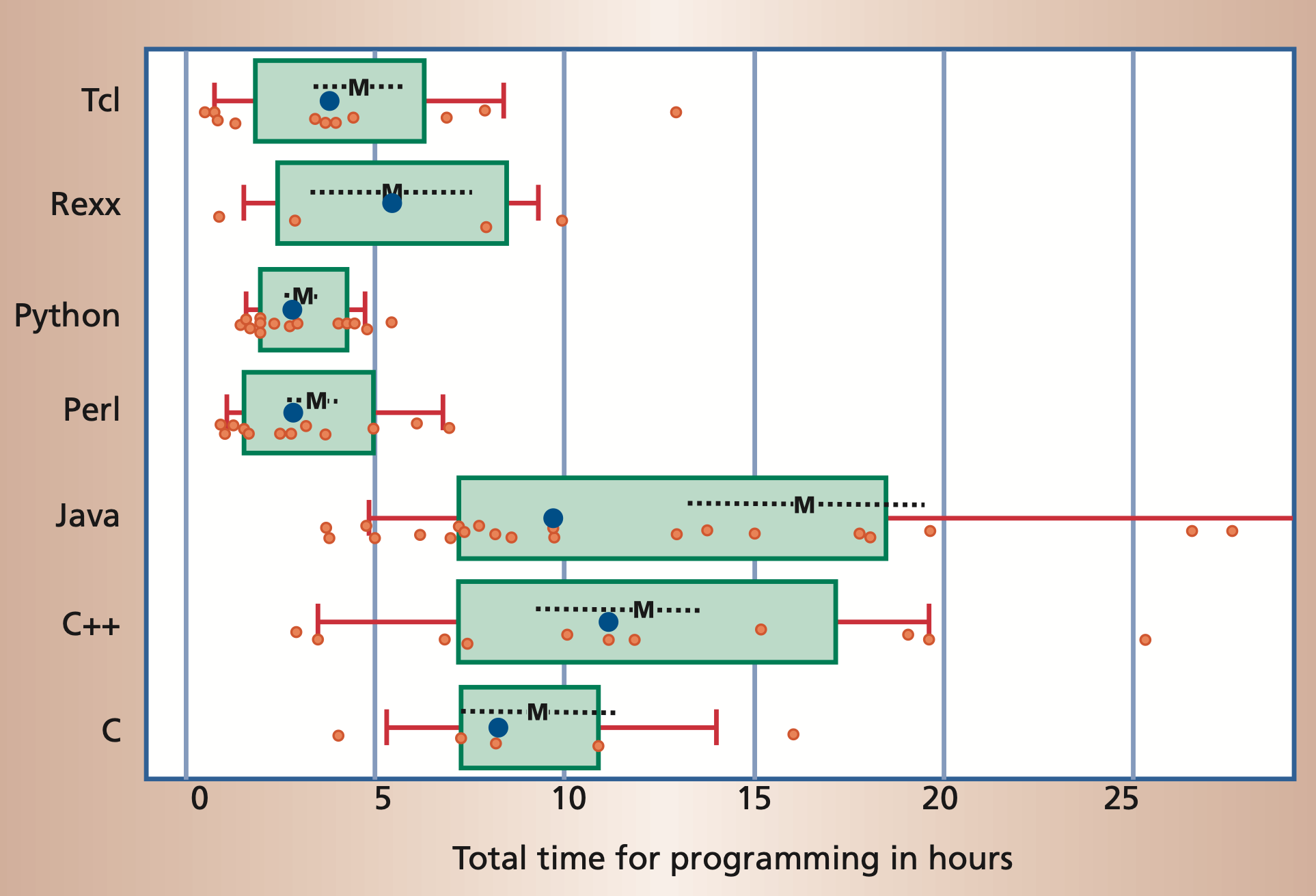

Moreover, it is often possible to accomplish the same task in significantly

less time in a scripting language than it takes using a compiled language.

But Python is slow!?

A common argument that is raised against using Python is that it is a comparatively slow language. There is some truth to this statement. Therefore, we want to understand one of the reasons why this is so and then explain why (in most cases) this is not a problem for us.

Python is an interpreted language.

Python itself is a C program that reads the source code of a text file, interprets it and executes it. This is in contrast to a compiled language like C, C++, Rust, etc. where the source code is compiled to machine code. The compiler has the ability to do lots of optimizations to the code which leads to a shorter runtime. This behavior can be shown by a simple example. Let's assume we have a naïve implementation to sum up all odd numbers up to 100 million:

s = 0

for i in range(100_000_000):

if i % 2 == 1:

s += i

This code takes about 8 seconds on my computer (M1 mac) to execute. Now we can implement the same algorithm in a compiled language to see the impact of the compiler. The following listing is written in a compiled language (Rust), but the details of this code and the programming language do not matter at this point:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let mut s: usize = 0; for i in 0..100_000_000 { if i % 2 == 1 { s += i; } } }

This code has actually no runtime at all and evaluates instantaneously.

The compiler is smart enough to understand that everything can be

computed at compile time and just inserts the value for the variable

s. This now makes it clear that compiled languages can make use of

methods that interpreted languages lack simply by virtue of their

approach. However, we have seen before that compiled languages usually

require more lines of code and more work. In addition, there are usually

much more concepts to learn.

Python can be very performant

During this lecture we will often use Python libraries like NumPy or Scipy for mathematical algorithms and linear algebra in particular. These packages bring two big advantages. On the one hand they allow the use of complicated algorithms very easily and on the other hand these packages are written in compiled languages like C or Fortran. This way we can benefit from the performance advantages without having to learn another possibly more complicated language.

How to interact with this website

This section gives an introduction on how to interact with the lecture notes. These are organized into chapters. Each chapter is a separate page. Chapters are nested into a hierarchy of sub-chapters. Typically, each chapter will be organized into a series of headings to subdivide a chapter.

Navigation

There are several methods for navigating through the chapters of a book.

The sidebar on the left provides a list of all chapters. Clicking on any of the chapter titles will load that page.

The sidebar may not automatically appear if the window is too narrow, particularly on mobile displays. In that situation, the menu icon (three horizontal bars) at the top-left of the page can be pressed to open and close the sidebar.

The arrow buttons at the bottom of the page can be used to navigate to the previous or the next chapter.

The left and right arrow keys on the keyboard can be used to navigate to the previous or the next chapter.

Top menu bar

The menu bar at the top of the page provides some icons for interacting with the notes.

| Icon | Description |

|---|---|

| Opens and closes the chapter listing sidebar. | |

| Opens a picker to choose a different color theme. | |

| Opens a search bar for searching within the book. | |

| Instructs the web browser to print the set of notes. |

Tapping the menu bar will scroll the page to the top.

Search

The lecture notes have a built-in search system.

Pressing the search icon () in the menu bar or pressing the S key on the keyboard will open an input box for entering search terms.

Typing any terms will show matching chapters and sections in real time.

Clicking any of the results will jump to that section. The up and down arrow keys can be used to navigate the results, and enter will open the highlighted section.

After loading a search result, the matching search terms will be highlighted in the text.

Clicking a highlighted word or pressing the Esc key will remove the highlighting.

Code blocks

Code blocks contain a copy icon , that copies the code block into your local clipboard.

Here's an example:

print("Hello, World!")

We will often use the assert statement in code listings to show you

the value of a variable. Since the code blocks in this document are not

interactive (you can not simply execute them in your browser), it is

not possible to print the value of the variable to the screen.

Therefore, we ensure for you that all code blocks in these lecture notes

run without errors and in this way we can represent the value of a

variable through the use of assert.

The following code block for example shows that the variable a has

the value 2:

a = 2

assert a == 2

If the condition would evaluate to False, the assert statement would

raise an AssertionError.

Fundamentals

In the following sections we will explain the concept of bitwise operators, but first lay the necessary foundations. Our goal is to show what bitwise operators do and what they can be useful for. Afterwards, we also want to show the possibility and importance of unit tests. At the end of this chapter you should be able to answer the following questions:

- How are numbers represented in the computer?

- What is the difference in the representation between signed and unsigned numbers/integers?

- Which operations exist to compare the state of two bits?

- What are bitwise operators?

- What are unit tests? And why are they important?

Binary Numbers

When working with any kind of digital electronics it is important to understand that numbers are represented by two levels which can represent a one or a zero. The number system based on ones and zeroes is called the binary system (because there are only two possible digits). Before discussing the binary system, a review of the decimal (ten possible digits) system is helpful, because many of the concepts of the binary system will be easier to understand when introduced alongside their decimal counterpart.

Decimal System

You should all have some familiarity with the decimal system. For instance, to represent the positive integer one hundred and twenty-five as a decimal number, we can write (with the postive sign implied):

$$ 125_{10} = 1 \cdot 100 + 2 \cdot 10 + 5 \cdot 1 = 1 \cdot 10^2 + 2 \cdot 10^1 + 5 \cdot 10^0 $$

The subscript 10 denotes the number as a base 10 (decimal) number.

There are some important observations:

- To multiply a number by 10 you can simply shift it to the left by one digit, and fill in the rightmost digit with a 0 (moving the decimal place one to the right).

- To divide a number by 10, simply shift the number to the right by one digit (moving the decimal place one to the left).

- To see how many digits a number needs, you can simply take the logarithm (base 10) of the absolute value of the number, and add 1 to it. The integral part of the result will be the number of digits. For instance, \(\log_{10}(33) + 1 = 2.5.\)

Binary System (of positive integers)

Binary representations of positive integers can be understood in the same way as their decimal counterparts. For example

$$ 86_{10}=1 \cdot 64+0 \cdot 32+1 \cdot 16+0 \cdot 8+1 \cdot 4+1 \cdot 2+0 \cdot 1 $$

This can also be written as:

$$ 86_{10}=1 \cdot 2^{6} +0 \cdot 2^{5}+1 \cdot 2^{4}+0 \cdot 2^{3}+1 \cdot 2^{2}+1 \cdot 2^{1}+0 \cdot 2^{0} $$ or

$$ 86_{10}=1010110_{2} $$

The subscript 2 denotes a binary number. Each digit in a binary number is called a bit. The number 1010110 is represented by 7 bits. Any number can be broken down this way, by finding all of the powers of 2 that add up to the number in question (in this case \(2^6\), 2\(^4\), 2\(^2\) and 2\(^1\)). You can see this is exactly analogous to the decimal deconstruction of the number 125 that was done earlier. Likewise we can make a similar set of observations:

- To multiply a number by 2 you can simply shift it to the left by one digit, and fill in the rightmost digit with a 0.

- To divide a number by 2, simply shift the number to the right by one digit.

- To see how many digits a number needs, you can simply take the logarithm (base 2) of the number, and add 1 to it. The integral part of the result is the number of digits. For instance, \(\log_{2}(86) + 1 = 7.426.\) The integral part of that is 7, so 7 digits are needed. With \(n\) digits, \(2^n\) unique numbers (from 0 to \(2^n - 1\)) can be represented. If \(n=8\), 256 (\(=2^8\)) numbers can be represented (0-255).

This counter shows how to count in binary from zero through thirty-one.

Binary System of Signed Integers

We will not be using a minus sign (\(-\)) to represent negative numbers. We would like to represent our binary numbers with only two symbols, 0 and 1. There are a few ways to represent negative binary numbers. We will discuss each of these in the following subsections.

Note: Unlike other programming languages, where different types of integers exist (signed, unsigned, different number of bits), in Python there is only one integer type (

int). This is a signed integer type with arbitrary precision. This means, the integer has not a fixed number of bits to represent the number, but will dynamically use as many bits as needed to represent the number. Therefore, integer overflows cannot occur in Python. This doesn't hold forfloats, which have fixed size of 64 bit and can overflow.

Sign and Magnitude

The most significant bit (MSB) determines if the number is positive (MSB is 0) or negative (MSB is 1). All following bits are the so called magnitude bits. This means that a 8 bit signed integer can represent all numbers from -127 to 127 (\(-2^6\) to \(2^6\)). Except for the MSB, all positive and negative numbers share the same representation.

Visualization of the Sign and Magnitude representation of the decimal number +13.

In the case of a negative number, the only difference is that the first bit (the MSB) is inverted, as shown in the following Scheme.

Visualization of the Sign and Magnitude representation of the decimal number -31

Although this representation seems very intimate and simple, there are multiple consequences and problems that it makes:

- There are two ways to represent zero,

0000 0000and1000 0000. - Addition and subtraction require different behaviors depending on the sign bit.

- Comparisons (e.g. greater, less, ...) also require inspection of the sign bit.

This approach is directly comparable to the common way of showing a sign (placing a "+" or "−" next to the number's magnitude). This kind of representation was only used in early binary computers and was replaced by representations that we will discuss in the following.

Ones' Complement

To overcome the limitations of the Sign and Magnitude representation, another representation was developed with the following idea in mind: One wants to flip the sign of an integer by inverting all bits.

This inversion is also known as taking the complement of the bits. The implication of this idea is, that the first bit, the MSB, also represents just the sign as in the Sign and Magnitude case. However, the decimal value of all other bits are now dependent of the MSB bit state. It might be easier to understand this behaviour by a simple example that outlines the motivation again.

We want that our binary representation behaves like:

The advantage of this representation is that for adding two numbers, one can do a conventional binary addition, but it is then necessary to do an end-around carry: that is, add any resulting carry back into the resulting sum. To see why this is necessary, consider the following example showing the case of the following addition $$ −1_{10} + 2_{10} $$

or

$$ 1111 1110_2 + 0000 0010_2 $$

In the previous example, the first binary addition gives 00000000, which

is incorrect. The correct result (00000001) only appears when the carry

is added back in.

A remark on terminology: The system is referred to as ones' complement because the negation of a positive value x (represented as the bitwise NOT of x, we will discuss the bitwise NOT in the following sections) can also be formed by subtracting x from the ones' complement representation of zero that is a long sequence of ones (−0).

Two's Complement

In the two's complement representation, a negative number is represented by the bit pattern corresponding to the bitwise NOT (i.e. the "complement") of the positive number plus one, i.e. to the ones' complement plus one. It circumvents the problems of multiple representations of 0 and the need for the end-around carry of the ones' complement representation.

This can also be thought of as the most significant bit representing the inverse of its value in an unsigned integer; in an 8-bit unsigned byte, the most significant bit represents the number 128, where in two's complement that bit would represent −128.

In two's-complement, there is only one zero, represented as 00000000. Negating a number (whether negative or positive) is done by inverting all the bits and then adding one to that result.

Addition of a pair of two's-complement integers is the same as addition of a pair of unsigned numbers. The same is true for subtraction and even for N lowest significant bits of a product (value of multiplication). For instance, a two's-complement addition of 127 and −128 gives the same binary bit pattern as an unsigned addition of 127 and 128, as can be seen from the 8-bit two's complement table.

Two's complement is the representation that Python uses for it's type

int.

Logic Gates

Truth tables show the result of combining inputs using a given operator.

NOT Gate

The NOT gate, a logical inverter, has only one input. It reverses the logic state. If the input is 0, then the output is 1. If the input is 1, then the output is 0.

| INPUT | OUTPUT |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 |

AND Gate

The AND gate acts in the same way as the logical "and" operator. The following truth table shows logic combinations for an AND gate. The output is 1 only when both inputs are 1, otherwise, the output is 0.

| A | B | Output |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

OR Gate

The OR gate behaves after the fashion of the logical inclusive "or". The output is 1 if either or both of the inputs are 1. Only if both inputs are 0, then the output is 0.

| A | B | Output |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

NAND Gate

The NAND gate operates as an AND gate followed by a NOT gate. It acts in the manner of the logical operation "and" followed by negation. The output is 0 if both inputs are 1. Otherwise, the output is 1.

| A | B | Output |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

NOR Gate

The NOR gate is a combination of OR gate followed by a NOT gate. Its output is 1 if both inputs are 0. Otherwise, the output is 0.

| A | B | Output |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

XOR Gate

The XOR (exclusive-OR) gate acts in the same way as the logical "either/or." The output is 1 if either, but not both, of the inputs are 1. The output is 0 if both inputs are 0 or if both inputs are 1. Another way of looking at this circuit is to observe that the output is 1 if the inputs are different, but 0 if the inputs are the same.

| A | B | Output |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

XNOR Gate

The XNOR (exclusive-NOR) gate is a combination of XOR gate followed by a NOT gate. Its output is 1 if the inputs are the same, and 0 if the inputs are different.

| A | B | Output |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

Bitwise Operators

Bitwise operators are used to manipulate the states of bits directly. In Python (>3.5) there are 6 bitwise operators defined:

| Operator | Name | Example | Output (x=7, y=2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| << | left bitshift | x << y | 28 |

| >> | right bitshift | x >> y | 1 |

| & | bitwise and | x & y | 2 |

| | | bitwise or | x | y |

| ~ | bitwise not | ~x | -8 |

| ^ | bitwise xor | x ^ y | 5 |

Left Bitshift

Returns x with the bits shifted to the left by y places (and new bits on the right-hand-side are zeros). This is the same as multiplying \(x\) by \(2^y\).

The easiest way to visualize this operation is to consider a number that consists of only a single 1 in binary representation. If we now simply shift a 1 to the left three times in succession, we get the following:

assert (1 << 1) == 2 # ..0001 => ..0010

assert (2 << 1) == 4 # ..0010 => ..0100

assert (4 << 1) == 8 # ..0100 => ..1000

But we can also do this operation with just one call:

assert (1 << 3) == 8 # ..0001 => ..1000

Of course, we can also apply this operation to any other number:

assert (3 << 2) == 12 # ..0011 => ..1100

Right Bitshift

Returns x with the bits shifted to the right by y places. This is the same as dividing \(x\) by \(2^y\).

assert (8 >> 1) == 4 # ..1000 => ..0100

assert (4 >> 1) == 2 # ..0100 => ..0010

assert (2 >> 1) == 1 # ..0010 => ..0001

As we did with the bit shift to the left side, we can also shift a bit multiple times to the right:

assert (8 >> 3) == 1 # ..1000 => ..0001

Or apply the operator to any other number that is not a multiple of 2.

assert (11 >> 2) == 2 # ..1011 => ..0010

Bitwise AND

Does a "bitwise and". Each bit of the output is 1 if the corresponding bit of \(x\) AND \(y\) is 1, otherwise it is 0.

assert (1 & 2) == 0 # ..0001 & ..0010 => ..0000

assert (7 & 5) == 5 # ..0111 & ..0101 => ..0101

assert (12 & 3) == 0 # ..1100 & ..0011 => ..0000

Bitwise OR

Does a "bitwise or". Each bit of the output is 0 if the corresponding bit of \(x\) OR \(y\) is 0, otherwise it's 1.

assert (1 | 2) == 3 # ..0001 & ..0010 => ..0011

assert (7 | 5) == 7 # ..0111 & ..0101 => ..0111

assert (12 | 3) == 15 # ..1100 & ..0011 => ..1111

Bitwise NOT

Returns the complement of \(x\) - the number you get by switching each 1 for a 0 and each 0 for a 1. This is the same as \(-x - 1\).

assert ~0 == -1

assert ~1 == -2

assert ~2 == -3

assert ~3 == -4

Bitwise XOR

Does a "bitwise exclusive or". Each bit of the output is the same as the corresponding bit in \(x\) if that bit in \(y\) is 0, and it is the complement of the bit in x if that bit in y is 1.

assert (1 ^ 2) == 3 # ..0001 & ..0010 => ..0011

assert (7 ^ 5) == 2 # ..0111 & ..0101 => ..0010

assert (12 ^ 3) == 15 # ..1100 & ..0011 => ..1111

Arithmetic Operators

Arithmetic operators are used to perform mathematical operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. In Python (>3.5) there are 7 arithmetic operators defined:

| Operator | Name | Example | Output (x=7, y=2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| + | Addition | x + y | 9 |

| - | Subtraction | x - y | 5 |

| * | Multiplication | x * y | 14 |

| / | Division | x / y | 3.5 |

| // | Floor division | x // y | 3 |

| % | Modulus | x % y | 1 |

| ** | Exponentiation | x ** y | 49 |

Addition

The + (addition) operator yields the sum of its arguments.

The arguments must either both be numbers or both be sequences of the same type. Only in the former case, the numbers are converted to a common type and a arithmetic addition is performed. In the latter case, the sequences are concatenated, e.g.

a = [1, 2, 3]

b = [4, 5, 6]

assert (a + b) == [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

Subtraction

The - (subtraction) operator yields the difference of its arguments.

The numeric arguments are first converted to a common type.

Note: In contrast to the addition, the subtraction operator cannot be applied to sequences.

Multiplication

The * (multiplication) operator yields the product of its arguments.

The arguments must either both be numbers, or one argument must be an integer and the other must be a sequence.

In the former case, the numbers are converted to a common type and then multiplied together.

In the latter case, sequence repetition is performed; e.g.

a = [1, 2]

assert (3 * a) == [1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2]

Note: a negative repetition factor yields an empty sequence; e.g.

a = 3 * [1, 2]

assert (-2 * a) == []

Division & Floor division

The / (division) and // (floor division) operators yield the quotient of their arguments.

The numeric arguments are first converted to a common type.

Note: Division of integers yields a float, while floor division of integers results in an integer;

the result is that of mathematical division with the floor function applied to the result.

Division by zero raises a ZeroDivisionError exception.

Modulus

The % (modulo) operator yields the remainder from the division of the first argument by the second.

The numeric arguments are first converted to a common type.

A zero right argument raises the ZeroDivisionError exception.

The arguments may even be floating point numbers, e.g.,

import math

assert math.isclose(3.14 % 0.7, 0.34)

# since

assert math.isclose(3.14, 4*0.7 + 0.34)

The modulo operator always yields a result with the same sign as its second operand (or zero); the absolute value of the result is strictly smaller than the absolute value of the second operand.

Note: As you may have noticed in the listing above, we did not use the comparison operator

==to test the equality of two floats. Instead we imported themathpackage and used the built-in isclose function. If you want to read more detailed information about float representation errors the following blog post can be recommended.

Exponentiation

The ** (power) operator has the same semantics as the built-in pow() function, when called with two arguments:

it yields its left argument raised to the power of its right argument. The numeric arguments are first converted to a common type.

The result type is that of the arguments after coercion;

if the result is not expressible in that type (as in raising an integer to a negative power)

the result is expressed as a float (or complex).

In an unparenthesized sequence of power and unary operators, the operators are evaluated from right to left

(this does not constrain the evaluation order for the operands), e.g.

assert 2**2**3 == 2**(2**3) == 2**8 == 256

Implementation: Arithmetic Operators

All arithmetic operators can be implemented using bitwise operators. While addition and subtraction are implemented through hardware, the other operators are often realized via software. In this section, we shall implement multiplication and division for positive integers using addition, subtraction and bitwise operators.

Implementation: Multiplication

The multiplication of integers may be thought as repeated addition; that is, the multiplication of two numbers is equivalent to the following sum: $$ A \cdot B = \sum_{i=1}^{A} B $$ Following this idea, we can implement a naïve multiplication:

def naive_mul(a, b):

r = 0

for i in range(0, a):

r += b

return r

Although we could be smart and reduce the number of loops by choosing the smaller one to be the multiplier, the number of additions always grows linearly with the size of the multiplier. Ignoring the effect of multiplicand, this behavior is called linear-scaling, which is often denoted as \(\mathcal{O}(n)\).

Can we do better?

We have learned that multiplication by powers of 2 can be easily realized by

the left shift operator <<. Since every integer can be written as sum of

powers of 2, we may try to compute the necessary products of the multiplicand

with powers of 2 and sum them up. We shall do an example: 11 * 3.

assert (2**3 + 2**1 + 2**0) * 3 == 11 * 3

assert (2**3 * 3 + 2**1 * 3 + 2**0 *3) == 11 * 3

assert (3 << 3) + (3 << 1) + 3 == 11 * 3

To implement this idea, we can start from the multiplicand (b) and check the

least-significant-bit (LSB) of the multiplier (a). If the LSB is 1, this power of

2 is present in a and b will be added to the result. If the LSB is 0, this power is

not present in a and nothing will be done. In order to check the second LSB of a

and perhaps add 2 * b, we can just right shift a. In this way the second LSB

will become the new LSB and b needs to be multiplied by 2 (left shift).

This algorithm is illustrated for the example above as:

| Iteration | a | b | r | Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1011 | 000011 | 000000 | r += b, b <<= 1, a >>= 1 |

| 1 | 0101 | 000110 | 000011 | r += b, b <<= 1, a >>= 1 |

| 2 | 0010 | 001100 | 001001 | b <<= 1, a >>= 1 |

| 3 | 0001 | 011000 | 001001 | r += b, b <<= 1, a >>= 1 |

| 4 | 0000 | 110000 | 100001 | Only zeros in a. Stop. |

An example implementation is given in the following listing:

def mul(a, b):

r = 0

for _ in range(0, a.bit_length()):

if a & 1 != 0:

r += b

b <<= 1

a >>= 1

return r

This new algorithm should scale with the length of the binary representation of the multiplier, which grows logarithmically with its size. This is denoted as \(\mathcal{O}(\log(n))\).

To show the difference between these two algorithms, we can write a function

to time their executions. The following example uses the function

perf_counter from time module:

from random import randrange

from time import perf_counter

def time_multiplication(func, n, cycles=1):

total_time = 0.0

for i in range(0, cycles):

a = randrange(0, n)

b = randrange(0, n)

t_start = perf_counter()

func(a, b)

t_stop = perf_counter()

total_time += (t_stop - t_start)

return total_time / float(cycles)

The execution time per execution for different sizes are listed below:

n | naive_mul / μs | mul / μs |

|---|---|---|

10 | 0.48 | 0.80 |

100 | 2.83 | 1.56 |

1 000 | 28.83 | 1.88 |

10 000 | 224.33 | 2.02 |

100 000 | 2299.51 | 2.51 |

Although the naïve algorithm is faster for \(a,b \leq 10\), its time

consumption grows rapidly when a and b become larger. For even larger

numbers, it will quickly become unusable. The second algorithm, however,

scales resonably well to be applied for larger numbers.

Implementation: Division

Just like for multiplication, the integer (floor) division may be treated as repeated subtractions. The quotient \( \lfloor A/B \rfloor \) tells us how often \(B\) can be subtracted from \(A\) before it becomes negative.

The naïve floor division can thus be implemented as:

def naive_div(a, b):

r = -1

while a >= 0:

a -= b

r += 1

return r

Just like naïve multiplication, this division algorithm scales linearly with the size of dividend, if the effect of divisor is ignored.

Can we do better?

In school, we have learned to do long divisions. This can also be done

using binary numbers. We at first left-align the divisor b with the

dividend a and compare the sizes of the overlapping part. If the divisor is

smaller, it goes once into the dividend. Therefore, the quotient at that bit

becomes 1 and the dividend is subtracted from the part of divisor. Otherwise, this

quotient bit will be 0 and no subtraction takes place. Afterwards,

the dividend is right-shifted and the whole process repeated.

This algorithm is illustrated in the following table for the example 11 // 2:

| Iteration | a | b | r | Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| preparation | 1011 | 0010 | 0000 | b <<= 2 |

| 0 | 1011 | 1000 | 0000 | a -= b, r.2 = 1, b >>= 1 |

| 1 | 0011 | 0100 | 0100 | b >>= 1 |

| 2 | 0011 | 0010 | 0100 | a -= b, r.0 = 1, b >>= 1 |

| 3 | 0001 | 0001 | 0101 | Value of b smaller than initial. Stop. |

An example implementation is given in the following listing:

def div(a, b):

n = a.bit_length()

tmp = b << n

r = 0

for _ in range(0, n + 1):

r <<= 1

if tmp <= a:

a -= tmp

r += 1

tmp >>= 1

return r

In this implementation, rather than setting the result bitwise like described

in the table above, it is initialized to 0 and appended with 0 or 1.

Also, the divisor is shifted by the bit-length of a instead of the difference

between a and b. This may increase the number of loops, but prevents

negative shifts, when bit-length of a is smaller than that of b.

This algorithm is linear in the bit-length of the dividend and thus a \(\mathcal{\log(n)}\) algorithm. Again, we want to quantify the performance of both algorithms by timing them.

Since the size of the divisor does not have a simple relation with the

execution time, we shall fix its size. Here we choose nb = 10. An example

function for timing is shown in the following listing:

from random import randrange

from time import perf_counter

def time_division(func, na, nb, cycles=1):

total_time = 0.0

for i in range(0, cycles):

a = randrange(0, na)

b = randrange(1, nb)

t_start = perf_counter()

func(a, b)

t_stop = perf_counter()

total_time += (t_stop - t_start)

return total_time / float(cycles)

Since we cannot divide by zero, the second argument, the divisor in this case, is chosen between 1 and n instead of 0 and n.

The execution time per execution for different sizes are listed below:

na | naive_div / μs | div / μs |

|---|---|---|

10 | 0.38 | 1.06 |

100 | 1.54 | 1.67 |

1 000 | 13.79 | 1.83 |

10 000 | 117.20 | 1.89 |

100 000 | 1085.89 | 2.24 |

Again, although the naïve method is faster for smaller numbers, its scaling prevents it from being used for larger numbers.

Edge Cases

Division by zero

Since division by zero is not defined, we should handle the case, where the

user calls the division function with 0 as divisor. Both implemented division algorithms

would be stuck in the while loop if 0 is

passed as the second argument and thus block further commands from being

executed. We obviously do not want this to happen.

In general, there are two ways to deal with "forbidden" values. The first

one is to raise an error, just like the build-in division operators, which

raises a ZeroDivisionError and halts the program. This is realized by adding

an if-condition at the beginning of the algorithm:

def div_err(a, b):

if b == 0:

raise ZeroDivisionError

...

Sometimes, however, we want the program to continue even after encountering

forbidden values. In this case, we can make the algorithm return something,

which is recognizable as invalid. This way, the user can be informed about

forbidden values through the outputs. One possible choice of such invalid

object is the None object and can be used like

def div_none(a, b):

if b == 0:

return None

...

Negative input

While implementing multiplication and division algorithms, the problems were only analyzed using non-negative integers. Inputs of negative integers may therefore lead to undefined behaviors. Again, we can raise an exception when this happens or utilise an invalid object. The following listings show both cases on the multiplication algorithm:

def mul_err(a, b):

if a < 0 or b < 0:

raise ValueError

...

def mul_none(a, b):

if a < 0 or b < 0:

return None

...

These lines can be directly added to division algorithms to deal with negative inputs.

Floating-point input

Just like in the case of negative input values, floating-point numbers as

inputs may also lead to undefined behaviors. Although the same input guards

can be applied to deal with floating-point numbers, a more sensible way would

be to convert the input values to integer using int function before

executing the algorithms.

Unit Tests

Everybody makes mistakes. Although the computer which executes programs does exactly what it is told to, we can make mistakes which may cause unexpected behavior. Therefore, proper testing is mandatory for any serious application. But I can just try some semi-randomly picked inputs after writing a function and see if I get the expected output, so ...

Why bother with writing tests?

First of all, if you share your program with other people, you have to persuade them that your program works properly. It is far more convincing if you have written tests, which they can run for themselves and see that nothing is out of order, than just tell them that you have tested some hand-picked examples.

Furthermore, functions are often rewritten multiple times to improve their performance. Since you want to ensure that the function still works properly after even the slightest modification, you will have to run the manual tests over and over again. The problem only gets worse for larger projects. Nested conditions, interdependent modules, multiple inheritance, just to name a few, will make manual testing a horrible choice; even the tiniest change could make you re-test every routine you have written.

So, to make your (and other's) life easier, just write tests.

What are unit tests?

Unit tests are typically automated tests to ensure that a part of a program (known as a "unit") behaves as intended. A unit could be an entire module, but it is more commonly an individual function or an interface, such as a class.

Since unit tests focus on a specific part of the program, it is very good at isolating individual parts and find errors in them. This can accelerate the debugging process, since only the code of units corresponding to failed tests have to be inspected. Exactly due to this isolating action however, unit tests cannot be used to evaluate every execution path in any but the most trivial programs and will not catch every error. Nevertheless, unit tests are really powerful and can greatly reduce the number of errors.

Writing example based tests

Note: Since we want to discover errors using unit tests, let us assume that we did not discuss anything about the edge cases for multiplication and division routines we have written.

Although Python has the built-in module unittest, another framework for

unit tests, pytest, exists,

which is easier to use and offers more functionalities. Therefore, we will

stick to pytest in this class. The thoughts presented however,

can be used with any testing framework.

When using jupyter-notebook, the module

ipytestcould be very handy. This can be installed withconda install -c conda-forge ipytest

Using conda, we can install pytest by executing

conda install -c anaconda pytest

in the console.

Suppose we have written mul function in the file multiplication.py

and div function in the file division.py, we can create the file

test_mul_div_expl.py in the same directory and import both functions as:

from multiplication import mul

from division import div

Unit test with examples

We choose one example for each function and write

def test_mul_example():

assert mul(3, 8) == 24

def test_div_example():

assert div(17, 3) == 5

where we call each function on the selected example and compare the output with the expected outcome.

After saving and exiting the document, we can execute

pytest

in the console. pytest will then find every .py files in the directory

which begins with test execute every function inside, which begins with

test. If we only want to execute test functions from one specific file,

say, test_mul_div_expl.py. we should call

pytest test_mul_div_expl.py

If any assert statement throws an exception, pytest will informs

us about it. In this case, we should see

================================ 2 passed in 0.10s ================================although the time may differ. It is good to see that the test passed. but

just because something works on one example, does not mean it always works.

One way to be more confident is to go through more examples. Instead of

writing the same function for all examples, we can use the function decorator

@parametrize provided by pytest.

Unit test with parametrized examples

We can use the function decorator by importing pytest and write

import pytest

@pytest.mark.parametrize(

'a, b, expected',

[(3, 8, 24), (7, 4, 28), (14, 11, 154), (8, 53, 424)],

)

def test_mul_param_example(a, b, expected):

assert mul(a, b) == expected

@pytest.mark.parametrize(

'a, b, expected',

[(17, 3, 5), (21, 7, 3), (31, 2, 15), (6, 12, 0)],

)

def test_div_param_example(a, b, expected):

assert div(a, b) == expected

The decorator @parametrize feeds the test function with values and makes

testing with multiple examples easy. It will becomes tedious however, if

we want to try even more examples.

Unit test with random examples

By going through a large amount of randomly generated examples, we may

uncover rarely occuring errors. This method is not always available, since

the expected output must somehow be available. In this case however, we can

just use python's built-in * and // operator to verify our own

function.

The following listing shows tests for 50 examples:

from random import randrange

N = 50

def test_mul_random_example():

for _ in range(0, N):

a = randrange(1_000)

b = randrange(1_000)

assert mul(a, b) == a * b

def test_div_random_example():

for _ in range(0, N):

a = randrange(1_000)

b = randrange(1_000)

assert div(a, b) == a // b

Running pytest should probably give us 2 passes. To be more confident, we

can increase the number of loops to, say, 700. Now, calling pytest several

times, we might get something like

========================================= short test summary info ==========================================

FAILED test_mul_div.py::test_div_random_example - ZeroDivisionError: integer division or modulo by zero

======================================= 1 failed, 1 passed in 0.20s =======================================

This tells us that the ZeroDivisonError exception occured while running

test_div_param_example function. Some more information can be seen above

the summary, and it should look like

def test_div_random_example():

for _ in range(0, N):

a = randrange(1_000)

b = randrange(1_000)

> assert div(a, b) == a // b

E ZeroDivisionError: integer division or modulo by zero

The arrow in the second last line shows the code where the exception occured.

In this case, we have provided the floor division operator // with a zero

on the right side. We thus know that we should modify our own implementation

to handle this case.

We have found the error without knowing the detailed implementation of the functions. This is desired since human tends to overlook things when analyzing code and some special cases might not be covered by testing with just a few examples. Although with 700 loops, the test passes about 50 % of the time, if we increase the number of loops to several thousands or even higher, the test is almost guaranteed to fail and inform us about deficies in our functions.

The existence of a reference method is not only possible in our toy example,

but also occurs in realistic cases. A common case is an intuitive, easy and

less error-prone to implement method, which has a long runtime. A more

complicated implementation which runs faster can then be tested against this

reference method. In our case, we could use naive_mul and naive_div as

reference methods for mul and div, respectively.

But what if we really do not have a reference method to produced a large amount of expected outputs? The so called property based testing could help us in this case.

Writing property based tests

Instead of comparing produced with expected outputs, we could use

properties which the function must satisfy as the criteria.

Let us consider a function cat which takes two str as input and outputs

the concatenation of them. Using example based tests, we would feed the

function with different strings and compare the outputs, i.e.

@pytest.mark.parametrize('a, b, expected', [('Hello', 'World', 'HelloWorld')])

def test_cat_example(a, b, expected):

assert cat(a, b) == expected

With property based tests, however, we can use the property that the concatenated string must contain and only contain both inputs in the given order and nothing else. This yields the following listing:

@pytest.mark.parametrize('a, b', [('Hello', 'World')])

def test_cat_property(a, b):

out = cat(a, b)

assert a == out[:len(a)]

assert b == out[len(a):]

Although we used an example here, no expected output is needed. So in

principle we could use randomly generated strings. Because property based

tests are designed to test a large number of inputs, smart ways of choosing

inputs and finding errors have been developed. All of these are implemented

in the module Hypothesis,

which can be installed by calling

conda install -c conda-forge hypothesis

The package Hypothesis contains two key components. The first one is called

strategies. This module contains a range of functions which return a search

strategy; an object with methods that describe how to generate and simplify

certain kinds of values. The second one is the @given decorator, which takes

a test function and turns it into a parametrized one which, when called, will

run the test function over a wide range of matching data from the selected

strategy.

For multiplication, we could use the property that the product must divide both input, i.e.

assert r % a == 0

assert r % b == 0

But since we have a reference method, we can combine the best from two worlds: intuitive output comparison from example based testing and smart algorithms as well as lots of inputs from property based testing. The test function can thus be written like

@given(st.integers(), st.integers())

def test_mul_property(a, b):

assert mul(a, b) == a * b

Since this test is very similar to the test with randomly generated

examples, we expect it to pass too. Calling pytest, the test failed

however. Hypothesis gives us the following output:

Falsifying example: test_mul_property(

a=-1, b=1,

)

Of course! We did not have negative numbers in mind while implementing this

algorithm! But why did we not discover this problem with our last test?

In order to generate random inputs, we have used the function randrange,

which does not include negative numbers as possible outputs. This fact is

however easily overlooked. By using predefined, well-thought strategies,

we can minimize human-errors while designing tests.

After writing this problem down to fix it later, we can continue testing

by excluding negative numbers. This can be achieved by using min_value

argument of integer():

@given(st.integers(min_value=0), st.integers(min_value=0))

def test_mul_property_non_neg(a, b):

assert mul(a, b) == a * b

Using only non-negative integers, the test passes. We can now test

the div function by writing

@given(st.integers(), st.integers())

def test_div_property(a, b):

assert div(a, b) == a // b

This time, Hypothesis tells us

E hypothesis.errors.MultipleFailures: Hypothesis found 2 distinct failures.with

Falsifying example: test_div_property(

a=0, b=-1,

)

Falsifying example: test_div_property(

a=0, b=0,

)

From this, we can exclude negative dividends and non-positive divisors by writing

@given(st.integers(min_value=0), st.integers(min_value=1))

def test_div_property_no_zero(a, b):

assert div(a, b) == a // b

After this modification, the test passes. Hypothesis provides a large amount

of strategies

and adaptations,

with which very flexible tests can be created.

One might notice that the counterexamples raised by Hypothesis are all very

"simple". This is no coincidence but deliberately made. This process is called

shrinking

and tries to produce the most human readable counterexample.

To see this point, we shall implement a bad multiplication routine, which

breaks for a > 10 and b > 20:

def bad_mul(a, b):

if a > 10 and b > 20:

return 0

else:

return a * b

We then test this bad multiplication with

@given(st.integers(), st.integers())

def test_bad_mul(a, b):

assert bad_mul(a, b) == a * b

Hypotheses reports

Falsifying example: test_bad_mul(

a=11, b=21,

)

which are the smallest example which breaks the equality.

Symbolic Computation

You may also know computer algorithms as numerical algorithms, since the computer uses finite-precision floating-point numbers to approximate the result. Although the numerical result can be arbitrarily precise by using arbitrary-precision arithmetic, they are still an approximation.

As human, we use symbols to carry out computations analytically. This can also be realized on computers using symbolic computation. There are many so called computer algebra systems (CAS) out there and you might already be familiar with one from school, if you have used a graphing calculator there like the ones shown below.

But of course CAS are not limited to external devices but also available as software for normal computers. The most commonly used computer algebra systems are Mathematica and SageMath/SymPy. We will use Sympy in this course because it is open-source and a Python library compared to Mathematica. SageMath is based on Sympy and offers a number of additional functionalities, which we do not need in this class.

SymPy can be installed by executing:

conda install -c anaconda sympy

To illustrate the difference between numerical and symbolic computations,

we compare the output of square root functions from numpy and sympy.

The code

import numpy as np

print(np.sqrt(8))

produces 2.8284271247461903 as output, which is an approximation to the

true value of (\sqrt(8)), while

import sympy as sp

print(sp.sqrt(8))

produces 2*sqrt(2), which is exact.

Basic Operations

We strongly advise you to try out the following small code examples yourself, preferably in a Jupyter notebook. There you can easily see the value of the variables and the equations can be rendered as latex. Just write the SymPy variable at the end of Jupyter cell without calling the

Defining Variables

Before solving any problem, we start defining our symbolic variables.

SymPy provides the constructor sp.Symbol() for this:

x = sp.Symbol('x')

This defines the Python variable x as a SymPy Symbol with the representation

'x'. If you print the variable in a Jupyter cell, you should see a rendered

symbol like: \( x \).

Since it might be annoying to define a lot variables, SymPy provides a another

function, which can initalizes a arbitrary number of symbols.

x, y, t, omega = sp.symbols('x y t omega')

which is just a shorthand for

x, y, t, omega = [sp.Symbol(n) for n in ('x', 'y', 't', 'omega')]

Note that it is important to separate each symbol in the sp.symbols() call

with a space.

SymPy also provides often used symbols (latin and greek letters) as predefined

variables. They are located in the submodule called abc

and can be imported by calling

from sympy.abc import x, y, nu

Expressions

Now we can use these variables to define an expression. We first want to define the following expression: $$ x + 2 y $$ SymPy allows us to write this expression in Python as we would do on paper:

x, y = sp.symbols('x y')

f = x + 2 * y

If you now print f in Jupyter cell you should see the same rendered equation

as above.

Lets assume we want to multiply our expression not by \( x \). We can

just do the following:

g = x * f

Now, we can print g and should get:

$$

x (x + 2y)

$$

One may expect this expression to transform into

\(x^2 + 2xy\), but we get the factorized form instead. SymPy

only performs obvious simplifications automatically, since one might

prefer the expanded of the factorized form depending on the circumstances.

But we can easily switch between both representations using the

transformation functions expand and factor:

g_expanded = sp.expand(g)

If you print g_expanded you should see, the expanded form of the equation, like:

$$

x^2 + 2xy

$$

Factorization of g_expanded brings us back to where we started.

g_factorized = sp.factor(g_expanded)

with the following representation: $$ x (x + 2y) $$

If you are feeling lazy, you can use the function simplify.

SymPy will then try to figure out which form would be the most suitable.

We can also write more complicated functions using elementary functions:

t, omega = sp.symbols('t omega')

f = sp.sqrt(2) / sp.sympify(2) * sp.exp(-t) * sp.cos(omega*t)

Note that since the division operator / on a number produces

floating-point numbers, we should modify numbers with the function sympify.

When dealing with rationals like 2/5, we can use sp.Rational(2, 5) instead.

If you print f the rendered equation should look like:

$$

\frac{\sqrt{2} e^{-t} \cos \left( \omega t \right)}{2}

$$

On some platforms, you may get a nicely rendered expression. While some

platform does not support nice printing, you could try to turn it on by

executing

sp.init_printing(use_unicode=True)

before any printing. We can also turn our expression into a function with either one

f_func1 = sp.Lambda(t, f)

or multiple arguments

f_func2 = sp.Lambda((t, omega), f)

by using the Lambda function. In the first case printing of f_func1

should look like

$$

\left(t \mapsto \frac{\sqrt{2} e^{-t} \cos (\omega t)}{2}\right)

$$

while f_func2 should give you:

$$

\left((t, \omega) \mapsto \frac{\sqrt{2} e^{-t} \cos (\omega t)}{2}\right)

$$

As you see these are still symbolic expressions, but the Python object is

now a callable function with either one or two positional arguments.

This allows us to substitute e.g. the variable \( t \) with

a number:

f_func1(1)

This gives us: $$ \frac{\sqrt{2} \cos (\omega)}{2 e} $$ We can also call our second function, which takes 2 arguments (\(t\), and \(\omega\)).

f_func2( sp.Rational(1, 2), 1 )

Which will result in:

$$

\frac{\sqrt{2} \cos \left(\frac{1}{2}\right)}{2 e^{\frac{1}{2}}}

$$

Note: We have now eliminated all variables and are left with an exact number, but this still

a SymPy object. You might wonder, how we can transform this to a numerical value which we can

use by other Python modules. SymPy provides this transformation with the function

lambdify, this looks similar to the Lambda function and also returns a Python function, that

we can call. However, the returned value of this function is now numerical value.

import math

f_num = sp.lambdify((t, omega), f)

assert math.isclose(f_num(0, 1), math.sqrt(2)/2)

Calculus

Calculus is hard. So why not let the computer do it for us?

Limits

Let us start by

evaluating the limit

$$\lim_{x\to 0} \frac{\sin(x)}{x}$$

We first define our variable \( x \) and the expression inside on the

right hand side. Then we can use the method limit to evaluate the

limit for \( x \to 0 \).

x = sp.symbols('x')

f = sp.sin(x) / x

lim = sp.limit(f, x, 0)

assert lim == sp.sympify(1)

Even one-sided limits like $$ \lim_{x\to 0^+} \frac{1}{x} \mathrm{\ \ vs.\ } \lim_{x\to 0^-} \frac{1}{x} $$ can be evaluated.

f = sp.sympify(1) / x

rlim = sp.limit(f, x, 0, '+')

assert rlim == sp.oo

llim = sp.limit(f, x, 0, '-')

assert llim == -sp.oo

Derivatives

Suppose we want find the first derivative of the following function

$$f(x, y) = x^3 + y^3 + \cos(x \cdot y) + \exp(x^2 + y^2)$$

We first start by defining the expression on the right side. In the next

step we can call the diff function, which expects an expression as the

first argument. The second to last argument (you can use one or more)

are the symbolic variables by which the expression will be derivated.

x, y = sp.symbols('x y')

f = x**3 + y**3 + sp.cos(x * y) + sp.exp(x**2 + y**2)

f1 = sp.diff(f, x)

In this we create the first derivative of \( f(x, y) \) w.r.t \(x\). You should get: $$ x^{3}+y^{3}+e^{x^{2}+y^{2}}+\cos (x y) $$

We can also build the second and third derivative w.r.t. x:

f2 = sp.diff(f, x, x)

f3 = sp.diff(f, (x, 3))

Note that two ways of computing higher derivatives are presented here. Of course, it is also possible to create the first derivative w.r.t \( x\) and \(y\):

f4 = sp.diff(f, x, y)

Evaluating Derivatives (or any other expression)

Sometimes, we want to evaluate derivatives, or just any expression at

specified points. For this purpose, we could again use Lambda to convert

the expression into a function and inserting values by function calls. But

SymPy expressions have the subs method to avoid the detour:

f = x**3 + y**3 + sp.cos(x*y) + sp.exp(x**2 + y**2)

f3 = sp.diff(f, (x, 3))

g = f3.subs(y, 0)

h = f3.subs(y, x)

i = f3.subs(y, sp.exp(x))

j = f3.subs([(x, 1), (y, 0)])

This method takes a pair of arguments. The first one is the variable to be substituted and the second one the value. Note that the value can also be a variable or an expression. A list of such pairs can also be supplied to substitute multiple variables.

Integrals

Even the most challenging part in calculus (integrals) can be evaluated $$ \int \mathrm{e}^{-x} \mathrm{d}x $$

f = sp.exp(-x)

f_int = sp.integrate(f, x)

This evaluates to $$ -e^{-x} $$ Note SymPy does not include the constant of integration. But this can be added easily by oneself if needed.

A definite integral could be computed by substituting the integration variable

with upper and lower bounds using subs. But it is more straightforward to

just pass a tuple as the second argument to the integrate function:

Suppose we want to compute the definite integral

$$\int_{0}^{\infty} \mathrm{e}^{-x}\ \mathrm{d}x$$

one can write

f = sp.exp(-x)

f_dint = sp.integrate(f, (x, 0, sp.oo))

assert f_dint == sp.sympify(1)

which evaluates to 1.

Also multivariable integrals like $$ \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \mathrm{e}^{-x^2-y^2}\ \mathrm{d}x \mathrm{d}y $$ can be easily solved. In this case the integral

f = sp.exp(-x**2 - y**2)

f_dint = sp.integrate(f, (x, -sp.oo, sp.oo), (y, -sp.oo, sp.oo))

assert f_dint == sp.pi

evaluates to \( \pi \).

Application: Hydrogen Atom

We learned in the bachelor quantum mechanics class that the wavefunction of the hydrogen atom has the following form: $$ \psi_{nlm}(\mathbf{r})=\psi(r, \theta, \phi)=R_{n l}(r) Y_{l m}(\theta, \phi) $$ where \(R_{n l}(r) \) is the radial function and \(Y_{l m}\) are the spherical harmonics. The radial functions are given by $$ R_{n l}(r)=\sqrt{\left(\frac{2}{n a}\right)^{3} \frac{(n-l-1) !}{2 n[(n+l) !]}} e^{-r / n a}\left(\frac{2 r}{n a}\right)^{l}\left[L_{n-l-1}^{2 l+1}(2 r / n a)\right] $$ Here \(n, l\) are the principal and azimuthal quantum number. The Bohr radius is denoted by \( a\) and \( L_{n-l-1}^{2l+1} \) is the associated/generalized Laguerre polynomial of degree \( n - l -1\). We will work with atomic units in the following, so that \( a = 1\). With this we start by defining the radial function:

def radial(n, l, r):

n, l, r = sp.sympify(n), sp.sympify(l), sp.sympify(r)

n_r = n - l - 1

r0 = sp.sympify(2) * r / n

c0 = (sp.sympify(2)/(n))**3

c1 = sp.factorial(n_r) / (sp.sympify(2) * n * sp.factorial(n + l))

c = sp.sqrt(c0 * c1)

lag = sp.assoc_laguerre(n_r, 2 * l + 1, r0)

return c * r0**l * lag * sp.exp(-r0/2)

We can check if we have no typo in this function by simply calling it with the three symbols

n, l, r = sp.symbols('n l r')

radial(n, l, r)

In the next step we can define the wave function by building the product of the radial function and the spherical harmonics.

from sympy.functions.special.spherical_harmonics import Ynm

def wavefunction(n, l, m, r, theta, phi):

return radial(n, l, r) * Ynm(l, m, theta, phi).expand(func=True)

With this we have everything we need and we can start playing with wave functions of the Hydrogen atom. Let us begin with the simplest one, the 1s function \( \psi_{100} \).

n, l, m, r, theta, phi = sp.symbols('n l m r theta phi')

psi_100 = wavefunction(1, 0, 0, r, theta, phi)

We can now use what we learned in the previous chapter and evaluate for example the wavefunction in the limit of \(\infty\) $$ \lim_{r\to \infty} \psi_{100}(r, \theta, \phi) $$

psi_100_to_infty = sp.limit(psi_100, r, sp.oo)

assert psi_100_to_infty == sp.sympify(0)

This evaluates to zero, as we would expect. Now let's check if our normalization of the wave function is correct. For this we expect, that the following holds: $$ \int_{0}^{+\infty} \mathrm{d}r \int_{0}^{\pi} \mathrm{d}\theta \int_{0}^{2\pi} \mathrm{d}\phi \ r^2 \sin(\theta)\ \left| \psi_{100}(r,\theta,\phi) \right|^2 = 1 $$ We can easily check this, since we already learned how to calculate definite integrals.

dr = (r, 0, sp.oo)

dtheta = (theta, 0, sp.pi)

dphi = (phi, 0, 2*sp.pi)

norm = sp.integrate(r**2 * sp.sin(theta) * sp.Abs(psi_100)**2, dr, dtheta, dphi)

assert norm == sp.sympify(1)

Visualizing the wave functions of the H atom.

To visualize the wave functions we need to evaluate them on a finite grid.

Radial part of wave function.

For this example we will take a look at radial part of the first 4 s-functions. We start by defining them:

r = sp.symbols('r')

r10 = sp.lambdify(r, radial(1, 0, r))

r20 = sp.lambdify(r, radial(2, 0, r))

r30 = sp.lambdify(r, radial(3, 0, r))

r40 = sp.lambdify(r, radial(4, 0, r))

This gives us 4 functions that will return numeric values of the radial part at some radius \(r\). The radial electron probability is given by \(r^2 |R(r)|^2\). We will use these functions to evaluate the wave functions on a grid and plot the values with Matplotlib.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

r0 = 0

r1 = 35

N = 1000

r_values = np.linspace(r0, r1, N)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(8, 5))

ax.plot(r_values, r_values**2*r10(r_values)**2, color="black", label="1s")

ax.plot(r_values, r_values**2*r20(r_values)**2, color="red", label="2s")

ax.plot(r_values, r_values**2*r30(r_values)**2, color="blue", label="3s")

ax.plot(r_values, r_values**2*r40(r_values)**2, color="green", label="4s")

ax.set_xlim([r0, r1])

ax.legend()

ax.set_xlabel(r"distance from nucleus ($r/a_0$)")

ax.set_ylabel(r"electron probability ($r^2 |R(r)|^2$)")

fig.show()

Spherical Harmonics

In the next step, we want to graph the spherical harmonics. To do

this, we first import all the necessary modules and then define first the

symbolic spherical harmoncis, Ylm_sym and then the numerical function Ylm.

from sympy.functions.special.spherical_harmonics import Ynm

import sympy as sp

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib import cm

%config InlineBackend.figure_formats = ['svg']

l, m, theta, phi = sp.symbols("l m theta phi")

Ylm_sym = Ynm(l, m, theta, phi).expand(func=True)

Ylm = sp.lambdify((l, m, theta, phi), Ylm_sym)

The variable Ylm now contains a Python function with 4 arguments (l, m,

theta, phi) and returns the numeric value (complex number, type: complex)

of the spherical harmonics. To be able to display the function graphically,

however, we have to evaluate the function not only at one point, but on a

two-dimensional grid (\(\theta, \phi\)) and then display the values on this

grid. Therefore, we define the grid for \(\theta\) and \(\phi\) and evaluate

the \(Y_{lm} \) for each point on this grid.

N = 1000

theta = np.linspace(0, np.pi, N)

phi = np.linspace(0, 2*np.pi, N)

theta, phi = np.meshgrid(theta, phi)

l = 3

m = 0

Ylm_num = 1/2 * abs(Ylm(l, m, theta, phi) + Ylm(l, -m, theta, phi))

Now, however, we still have a small problem because we want to represent our data points in a Cartesian coordinate system, but our grid points are defined in spherical coordinates. Therefore it is necessary to transform the calculated values of Ylm into the Cartesian coordinate system. The transformation reads:

x = np.cos(phi) * np.sin(theta) * Ylm_num

y = np.sin(phi) * np.sin(theta) * Ylm_num

z = np.cos(theta) * Ylm_num

Now we have everything we need to represent the spherical harmonics in 3

dimensions. We do a little trick and map the data points to a number range from

0 to 1 and store these values in the variable colors. This allows us to

colorize the spherical harmonics with a colormap

from Matplotlib.

colors = Ylm_num / (Ylm_num.max() - Ylm_num.min())

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(10, 10))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection="3d")

ax.plot_surface(x, y, z, facecolors=cm.seismic(colors))

ax.set_xlim([-1, 1])

ax.set_ylim([-1, 1])

ax.set_zlim([-1, 1])

fig.show()

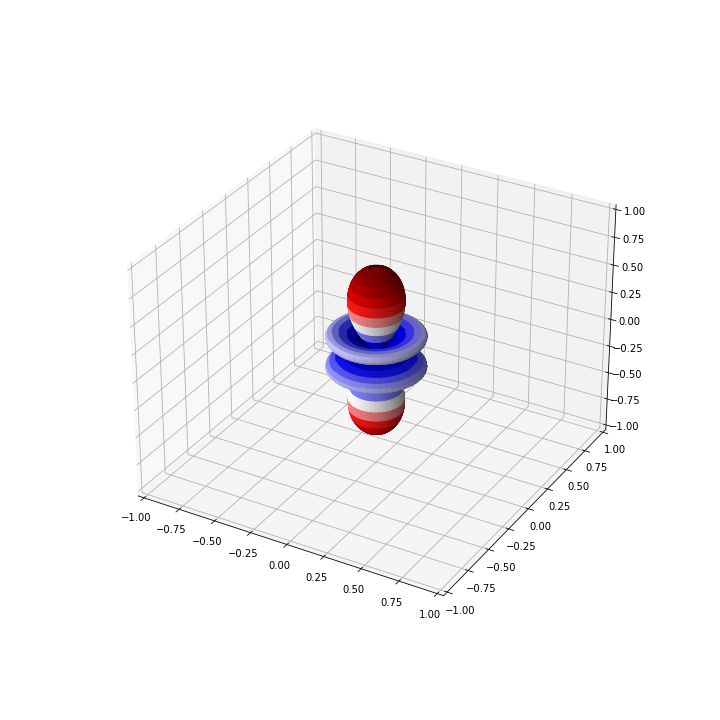

For the above example with \( Y_{30}\), the graph should look like

Application: Harmonic Oscillator

The quantum harmonic oscillator is described by wavefunctions $$ \psi_{n}(x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2^n n!}} \left( \frac{m \omega}{\pi \hbar} \right)^{1/4} \exp\left(-\frac{m\omega x^2}{2\hbar}\right) H_{n}\left( \sqrt{\frac{m\omega}{\hbar}} x \right) $$ where the functions \(H_{n}(z)\) are the physicists' Hermite polynomials: $$ H_{n}(z) = (-1)^n\ \mathrm{e}^{z^2} \frac{\mathrm{d}^n}{\mathrm{d}z^n} \left( \mathrm{e}^{-z^2} \right) $$ The corresponding energy levels are $$ E_{n} = \omega \left( n + \frac{1}{2} \right) $$

We now want to use SymPy to compute eigenenergies and eigenfunctions.

We start by importing sympy and neccesary variables:

import sympy as sp

from sympy.abc import x, m, omega, n, z

The eigenenergies are stright-forward to compute. One can just use the definition directly and substitute \(n\) by an integer, e.g. 5:

def energy(n):

e = omega * (n + sp.Rational(1, 2))

return e

e_5 = energy(5)

This outputs \(\frac{11}{2}\). Note that atomic units are used for simplicity.

In order to evaluate the wave function, we have to at first compute the Hermite polynomial. There are multiple ways to do it. The first is to use its definition directly and compute higher order derivatives of the exponential function:

def hermite_direct(n):

h_n = (-1)**n * sp.exp(z**2) * sp.diff(sp.exp(-z**2), (z, n))

h_n = sp.simplify(h_n)

return h_n

Another way is to use the recurrence relation $$ H_{n+1}(z) = 2zH_{n}(z) - H_{n}^{'}(z) $$ which can be implemented as a recursive function:

def hermite_recursive(n):

if n == 0:

return sp.sympify(1)

else:

return sp.simplify(

2 * x * hermite_recursive(n - 1) \

- sp.diff(hermite_recursive(n - 1), x)

)

For n = 5, both methods lead to the polynomial

$$ H_5(x) = 32 x^5 - 160 x^3 + 120 x$$

We can then use this to evaluate the wave function:

def wfn(n):

nf = (1/sp.sqrt(2**n * sp.factorial(n))) \

* ((m*omega)/sp.pi)**sp.Rational(1, 4)

expf = sp.exp(-(m*omega*x**2)/2)

hp = hermite_direct(n).subs(z, sp.sqrt(m*omega)*x)

psi_n = sp.simplify(nf * expf * hp)

return psi_n

psi_5 = wfn(5)

For a system with, say, \(m = 1\) and \(\omega = 1\), we can construct its wave function by

psi_5_param = psi_5.subs([(m, 1), (omega, 1)])

Further substituting x with any numerical value would evaluate the

wave function at that point. With the evalf method, we can obtain the

approximated numerical value:

psi_5_param_x_eval = psi_5_param.evalf(subs={x: sp.Rational(1, 2)})

print(psi_5_param_x_eval)

print(type(psi_5_param_x_eval))

Here, we compute the value of the wave function at \(x = \frac{1}{2}\).

We get 0.438575095003232 as the result. Note that the type of this object

is not float, but sympy.core.numbers.Float, which is a floating-point

number implementation with arbitrary precision. Actually, we can pass an

additional argument n to evalf to get an accuracy of n digits:

The listing

print(psi_5_param.evalf(n=50, subs={x: sp.Rational(1, 2)}))

for example, produces 0.43857509500323214478874587638315301825689754260515.

This type can be easily converted to python's built-in float by calling

float(). The arbitrary precision however, will be lost.

Sometimes one might just want to use SymPy to generate symbolic expressions

to be used in functions. Instead of typing the results in by hand, one could

use one of SymPy's built-in printers. Here, we shall use NumPyPrinter,

which converts a SymPy expression to a string of python code:

from sympy.printing.pycode import NumPyPrinter

printer = NumPyPrinter()

code = printer.doprint(psi_5_param)

code = code.replace('numpy', 'np')

print(code)

This output can be copied and used to evaluate \(\psi_{5}(x)\).

Since we often import NumPy with the alias np, numpy from the original

string is replaced.

Application: Particle in a Box

Problem

Determine the varianz und standard deviation for the location (\(x\)) and the momentum (\(p\)) for a particle in a box with a length of \(a\). Verify Heisenberg's uncertainty principle on this model.

The wave functions of a particle in a box is given by $$\psi_{n} = N \cdot \sin \left( \frac{n \pi}{a} x \right);\quad n \in \mathbb{N}$$ The variance of a quantity \(A\) is defined as $$\sigma_{A}^2 = \langle A^2 \rangle - \langle A \rangle^2$$

Solution

First, we import SymPy and define symbols with all necessary assumptions.

import sympy as sp

from sympy.physics.quantum.constants import hbar

x, N = sp.symbols('x N')

a = sp.Symbol('a', positive=True)

n = sp.Symbol('n', integer=True, positive=True)

(a) Define a function which performs integrals over \(x\) on the correct interval.

def integrate(expr):

return sp.integrate(expr, (x, 0, a))

(b) Find the normalization constant \(N\).

wf = N * sp.sin((n*sp.pi/a) * x)

norm = integrate(wf**2)

N_e = sp.solve(sp.Eq(norm, 1), N)[1]

The constant N_e should evaluate to \(\sqrt{2/a}\).

(c) Define the wave function \(\psi_{n}\).

psi = N_e * sp.sin((n*sp.pi/a) * x)

(d) Determine \(\sigma_{x}\).

x_mean = integrate(sp.conjugate(psi) * x * psi)

x_mean = sp.simplify(x_mean)

x_rms = integrate(sp.conjugate(psi) * x**2 * psi)

x_rms = sp.simplify(x_rms)

var_x = x_rms - x_mean**2

sigma_x = sp.sqrt(var_x)

The expectation value of \(x\) evaluates to $$ \langle x \rangle = \frac{a}{2} $$ and that of \(x^2\) evaluates to $$ \langle x^2 \rangle = \frac{a^2}{3} - \frac{a^2}{2 \pi^2 n^2}$$ The standard deviation of \(x\) is thus $$ \sigma_{x} = \sqrt{ \frac{a^2}{12} - \frac{a^2}{2 \pi^2 n^2} } $$

(e) Determine \(\sigma_{p}\).

p_mean = integrate(sp.conjugate(psi) * (-sp.I*hbar) * sp.diff(psi, x))

p_mean = sp.simplify(p_mean)

p_rms = integrate(sp.conjugate(psi) * (-sp.I*hbar)**2 * sp.diff(psi, x, x))

p_rms = sp.simplify(p_rms)

var_p = p_rms - p_mean**2

sigma_p = sp.sqrt(var_p)

The expectation value of \(p\) equals to \(0\) while that of \(p^2\) is $$ \langle p^2 \rangle = \frac{\pi^2 n^2}{a^2} $$ The standard deviation of \(p\) is therefore $$ \sigma_{p} = \frac{\pi n}{a} $$

(f) Compute the product \(\sigma_{x} \cdot \sigma_{p}\).

product = sigma_x * sigma_p

product = sp.simplify(prod)

p1 = prod.subs(n, 1)

This product equals to $$ \sigma_{x} \cdot \sigma_{p} = \frac{\sqrt{3 \pi^2 n^2 - 18}}{6} $$

For \(n = 1\), this expression takes on the value \( \frac{\sqrt{3\pi^2 - 18}}{6} \), which is approximately \(0.568\). For larger \(n\)'s, its value becomes larger. Therefore, Heisenberg's uncertainly principle holds for the particle in a box model.

Fourier Transformation

Let us consider periodic function with some period \(L>0\). Due to the fact that any linear combination of two periodic function with the same period is again a periodic function, the space of the periodic functions is mathematically a vector space. It is thus natural to seek for a basis in the space of periodic functions.

The archetypical periodic functions are the sine and cosine functions, that can be together compactly represented in the form of a complex exponential:

$$\varphi(x)=\exp(\mathrm{i}kx),$$

where \(k\) is some real parameter.

If we now impose the periodicity with the period \(L\) on the complex exponential we obtain the following relation which restricts the possible values of \(k\):

$$\varphi(x+L)=\varphi(x)\rightarrow\exp(\mathrm{i}kL)=1.$$

This relation will be full filled only for a discrete set of \(k-\)values that are defined by the relation:

$$k_{n}L=2\pi n\quad n\in\mathbb{Z}.$$

In this a discrete set of complex exponential functions all with the fundamental period of \(L\) can be constructed:

$$\varphi_{n}(x)=\exp\left(\frac{\mathrm{i} 2\pi n}{L}x\right)\quad n\in\mathbb{Z}$$

from ipywidgets import interact

import ipywidgets as widgets

L = 1.0

def plot_exp(n):

x = np.linspace(0, L, 500)

y= np.exp(2.0j*np.pi*n*x/L)

plt.xlim((-0.25, 1.25))

plt.plot(x, y.real, lw = 3.0)

plt.plot(x, y.imag, lw = 3.0)

interact(plot_exp, n=widgets.IntSlider(value=1, min=1, max=10, step=1))

The plot for \(n = 3\) is shown here:

Orthogonality of complex exponentials

We now show that the above defined periodic complex exponential constitute an orthonormal set of functions.

For this purpose we recall the definition of the complex inner product for two functions on an arbitrary interval [\(a,b\)], which is defined as:

$$ \langle f|g\rangle =\int_{a}^b \mathrm{d}x \ f^{ * } (x)g(x) $$

For two complex exponentials with indices \(m\) and \(n\) we have:

$$ \langle\varphi_{m}|\varphi_{n}\rangle=\int_{0}^{L} \mathrm{d}x \exp \left( \mathrm{i} \frac{2\pi}{L}(n-m)x \right) = \begin{cases} L & m=n \\ 0 & m \ne n \end{cases} $$

This can be compactly represented by introducing the Kronecker delta symbol:

$$\langle\varphi_{m}|\varphi_{n}\rangle=L\delta_{mn}$$

Thus, we now have a discrete set of orthonormal functions that can serve as a basis for representing arbitrary periodic function! The functions \(\varphi_{n}(x)\) are also called trigonometric polynomials since they can be expressed as:

$$\varphi_{n}(z)=z^{n}$$

Here \(z\) is a complex variable defined as:

$$z=\exp\left(\mathrm{i}\frac{2\pi x}{L}\right)$$

Approximating function by trigonometric polynomials

In the previous slide we have introduced the trigonometric polynomials. Now we introduce a formal definition. The function:

$$ \phi_{N}(x)=\sum_{j=0}^{N-1}c_{j}\exp\left(\mathrm{i}\frac{2\pi j}{L}x\right)$$

is called a trigonometric polynomial of the \(N-1\)-th order. The \(N-\)dimensional space of complex trigonometric polynomials is denoted by \(\mathbf{T}_ {N}^C \).